Our carnivore team are responsible for the daily care of the majority of our highly intelligent carnivores and apart from a focus on varying the meat-based diets, similar to what they would eat naturally, the keepers focus on building rapport with the animals and training them to make their care easier. Many of the carnivores are key species involved in our varied up-close encounters.

Follow us @hallsgapzoo

Happy International Women’s Day! 🌸 Today, we celebrate the strength, resilience, and achievements of women everywhere, but especially the amazing women we have on our team here at the Zoo who work through rain, hail and shine lifting bales of hay, carrying heavy branches, drilling holes, getting covered in dirt and mud and so much more to make sure our animals are cared for. Keep shining and keep supporting one another 💖💖

#internationalwomensday #lifteachotherup

🍀We are open every day this long weekend 🍀

Come and meet our animals, all our encounters are available this weekend (unless already booked), grab an ice cold drink from our food van 🧋 and enjoy seeing our animals exploring their enclosures in the sunshine ☀️

#longweekend #longweekendadventures #melbourne #hallsgapzoo #nationalpark #hallsgap #grampiansnationalpark #visitmelbourne

Fast Fact Friday’s subject for week 4 is our Meerkats, which is infact a type of mongoose, rather than a type of cat.

😎 Meerkats are highly observant and will use their long tail like a tripod with their legs to maintain a steady stance and higher vantage point.

😎 They live in groups of up to 30 individuals, where they will take turns in each role within the mob. This includes caring for the young, foraging or hunting, and sentry duty (standing guard for predators such snakes or eagles).

😎 Meerkat eyes are surrounded by dark circles to reduce glare from the sun. These ‘natural sunglasses’ allow them to spot predators easier in the open desert.

😎 They dig ‘bolt holes’ which are safe trenches for them to escape to in emergencies when they are foraging.

Our cheeky boys love their peas and corn. Hence, we had to name one of them Peas and his Brother was dubbed Corn.

✨✨Have you ever wanted to meet and have a photo with the Queen of selfies? ✨✨

We are very excited to announce that encounters with Ember our little Quokka are starting this long weekend.

Come and meet Ember and as you are chatting to her keepers about all things Quokkas you can pat her and try to get the best Quokka selfie you can.

Please email frontdesk@hallsgapzoo.com.au to book in as we only have limited spots available.

Encounter time will be at 3pm every day.

Participants must be 4 years and older (4-7 year olds must have paying guardian with them).

Today we celebrated World Wildlife Day. It is a day to recognise all our fauna and flora and the role they play in our ecosystems.

We are so lucky to have all these animals to share this planet with and without them our world changes, we need to make sure we do everything we can to protect them.

For week 3 of Fast Fact Friday, we are focused on Dragons, Gippsland Water Dragons to be precise.

🦎They typically live in groups with a dominant male, many females and young of all ages.

🦎 Water Dragons can lay up to 18 eggs in a single clutch.

🦎 Like the name suggests these reptiles love the water and can hold their breath underwater for over an hour and they use this tactic to evade predators.

Next time you are visiting see how many you can count.

Knuckles has the right idea spending the hot day having his lunch delivered to him while taking a swim. 📸 Supervisor Mila

Welcome to week 2 of Fast Fact Friday.

This week we are looking at the fascinating Wedge-Tailed Eagle.

🪶 Wedge-Tailed Eagles are Australia’s largest bird of prey and one of the world’s largest eagle, with an average wingspan of 2.3m.

🪶They build nests 1.8m across by 3m deep and will reuse these nests in following breeding seasons while continuing to add to them.

🪶Wedge-Tailed Eagle juveniles are a light brown colour and will darken as they get older.

Photo of our beautiful Hummer who is with us as he is unable to be returned to the wild after sustaining injuries from being hit by a car.

📸 Keeper Haylee

#nationalpark #hallsgapzoo #visitmelbourne #melbourne #grampiansnationalpark #hallsgap #wedgetailedeagle

Welcome to our first week of Fast Fact Friday.

Each week we will post new facts about a species we have here at the zoo. We want to share our beautiful animals with you and together we can explore what makes them so unique.

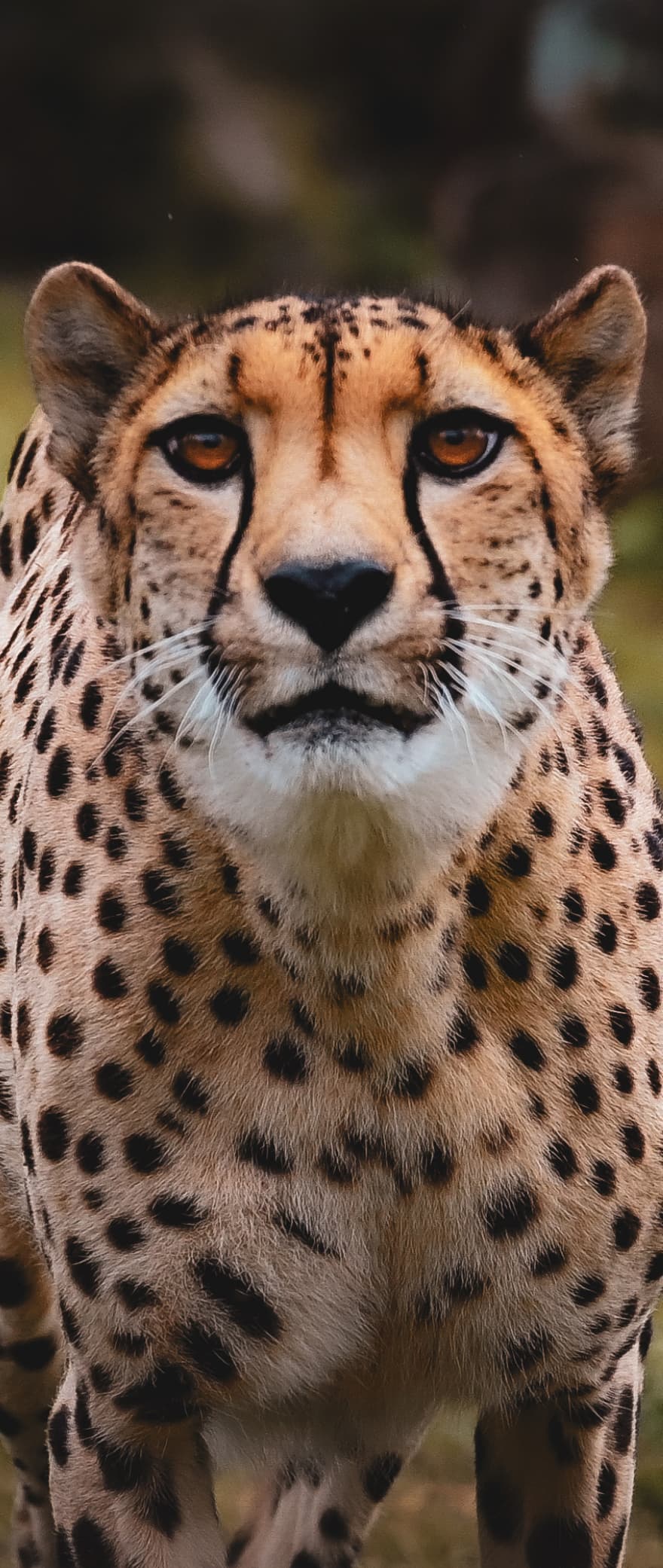

Obviously, we had to start with this animal. Who else? The Cheetah! The fastest land animal.

-Cheetahs can accelerate into a 112km/h sprint in only 3 seconds, but they cannot maintain high speeds for more than a minute.

- The Cheetah’s spots are designed for camouflage while hiding and during hunting and each Cheetah has a unique pattern in their spots.

-Cheetahs do not roar instead they purr just like our domestic cats at home.

Despite being very fast, they spend a lot of their time resting and lying in wait for the right moment to chase prey, you will see our boys lazing around in the sun and surveying their area.

What animals would you like to have featured in Fast Fact Friday? Comment below.

Running low on personal space after these school holidays? (Our Redneck Wallaby mum knows how you feel) Hop on in to the zoo today to let the kids run off some steam so they sleep well and are ready for the new school year. The weather is going to be perfect to see all the animals out and about.

📸 Keeper Sherrin

#grampians #grampiansvictoria #grampiansnationalpark #schoolholidays #schoolholidaysmelbourne #hallsgap #hallsgapzoo #hallsgapvictoria

Bristles would like to let everyone know we are open everyday this long weekend from 10am-5pm. Bring the kids for a nice day out before school is back. We have keeper talks planned, encounters will be running and our food van will be open for coffees, drinks and hot food. We can’t wait to see all of you . #hallsgapzoo #grampians #visitmelbourne #victoria #visitvictoria #redpanda

We would like to introduce our new babies. Firstly we have 2 baby elk calves that you might be lucky enough to get a glimpse of. Mum will usually keep the babies in the thick bush for the first few weeks to keep them safe and as they get older they start venturing out more, they are born with spots and without a scent so they don’t attract any predators.

We also have a beautiful baby Quokka keepers named Ember she is not on display just yet but be sure to keep an eye out on socials on when she will make her debut. #hallsgapzoo #grampians #visitmelbourne #victoria #visitvictoria #quokka #elk

Come and enjoy some up close encounters with our animals and while our keepers talk to you about facts and individual personalities you can:

😍Have a Red Panda walk across your lap,

😱Pat a rhino,

😄Hold a lizard,

🤭Feed a cheetah,

🤗Get kisses from the dingoes,

😮Feel small standing next to our giraffe

🥰Hold an otters hand

🤪Deal with the craziness of our meerkat mob

🤗Or walk our baby wombat

If you’ve had encounters what has been your favourite?

Check out the link below for more information and it is always best to pre book as some encounters are limited to only 2 people a day.

https://hallsgapzoo.com.au/encounters/

WE ARE OPEN!!!!

From Tuesday the 7th of January at 10am we officially reopen to visitors. It has been a long 17 days of being closed so our animals are so excited to see you all. Encounters will be up and running so please call to book or arrive early to avoid disappointment.

#hallsgapzoo #grampians #visitmelbourne